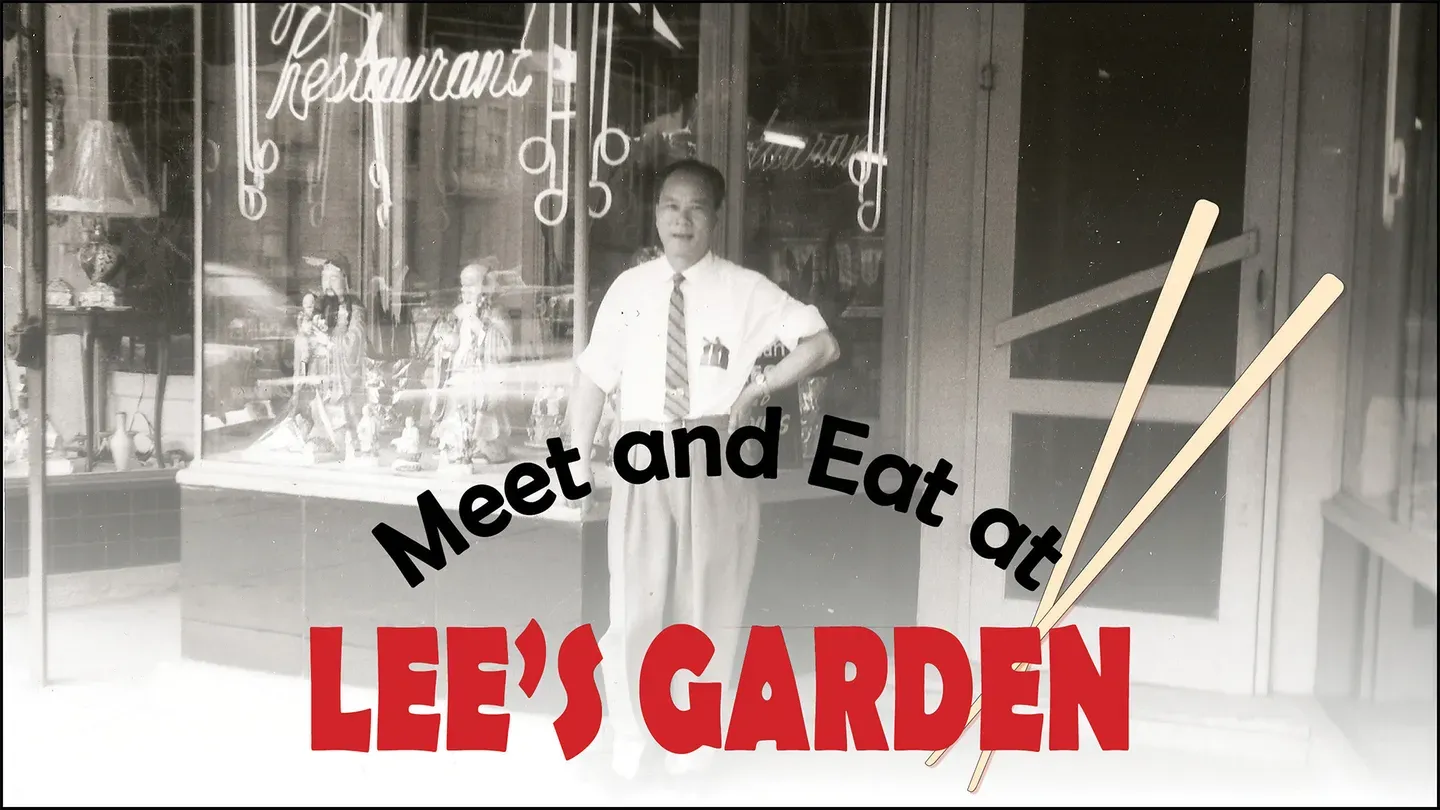

Meet and Eat at Lee's Garden

Special | 43m 56sVideo has Closed Captions

A daughter's recollection of her family’s Chinese Canadian restaurant and its community.

A daughter recalls her memories of her family’s restaurant Lee’s Garden, one of the first Chinese restaurants to open outside of Montreal’s Chinatown in the 1950s. Through interviews with former customers and families who owned other restaurants, the documentary explores how these early restaurants played an important role in the social history of Chinese and Jewish communities.

Meet and Eat at Lee's Garden is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television

Meet and Eat at Lee's Garden

Special | 43m 56sVideo has Closed Captions

A daughter recalls her memories of her family’s restaurant Lee’s Garden, one of the first Chinese restaurants to open outside of Montreal’s Chinatown in the 1950s. Through interviews with former customers and families who owned other restaurants, the documentary explores how these early restaurants played an important role in the social history of Chinese and Jewish communities.

How to Watch Meet and Eat at Lee's Garden

Meet and Eat at Lee's Garden is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

>> These are my strongest childhood memories -- not of playing with friends, birthday parties, or family vacations, but of answering the phone for delivery orders, greeting customers, and a hot, steamy kitchen.

But I treasure these memories.

♪ I'm the daughter of a restaurant owner, the youngest of three children.

In the Chinese community, instead of introducing me by my name, People would just say "Her father owns Lee's Garden."

My sister Nona and I made egg rolls with our mother every Sunday while my brother Paul waited on tables.

When I was older, I answered the phone and handled the cash register.

My family's life revolved around the restaurant.

It was open 365 days a year.

I worked every holiday, including Christmas and New Year's.

When I asked my dad about his childhood, he shrugged it off, saying there wasn't much to tell.

But whenever he talked with his friends, I listened quietly and learned a few details.

Now I wish I had asked for more.

My parents passed away years ago, and now it's too late.

Or is it?

When my friend Judy told me that Lee's Garden was a landmark in the Jewish community, a light bulb went off in my head.

I suddenly realized that the restaurant wasn't just my family's story, but was a part of the history of both the Chinese and Jewish communities, and that it was the key to my father's past.

>> You know, when I look back at my teen years, I don't remember a lot of the places that we would hang out.

I remember being at the Y. I remember being at Baron Byng after school.

But Lee's Garden was a special hangout place for all of us.

>> I probably started going to Lee's Garden when I was about 5 or 6 years old.

That was my first experience of tasting what we considered then ethnic food compared to what my mom made at home.

And we knew about your parents' restaurant because my dad had a snack bar in Park Avenue about less than a block away from there.

>> The whole area had a number of youth organizations.

Some of them I belonged to.

And this was a favorite restaurant to go to.

Park Avenue was one of the important streets in the area because it had a lot of shops and restaurants.

But at the same time, it was a street that became the boulevard to be seen, especially during holidays, so that whenever we had holidays, people would dress up in their fancy clothes and they would march on Park Avenue to be seen and to see what was happening.

So it was a very popular street, and Lee's Garden was located in the center of this boulevard.

>> Most of the people who went were going to the same high schools.

There were two high schools.

There was the Baron Byng High School, and there was another one that was more for the ritzy kids.

And they all went to the same places.

They all went to the same Park Avenue to hang out and they all went to Lee's Garden because it was the place to see and be seen.

>> My father, Gin Lee, was part of the generation known as head tax payers.

He paid $500 in 1921 to enter Canada, which today would be $7,255.

It's a history that the Chinese community commemorates every year.

>> Our association holds an ancestral ceremony every year.

This ancestral ceremony is basically to honor the first settlers that came to Canada that worked on the railway.

The early settlers that came to Canada, many of them ended up either owning laundries or restaurants.

They would be living and also doing their business in the same location.

The head tax was imposed after the railway -- the Canadian railway was built.

And the reason for this was the government wanted to restrict the number of Chinese immigrants coming into Canada.

I believe the original head tax was $50.

That was during the days of John A. Macdonald's government.

The tax was increased to $100 in the early 1900s.

Eventually, it went all the way up to $500.

The purpose of the lion dance is to awaken the spirits of our forefathers.

We then pay our respects with food offerings.

So the burning of the money is the present generation's offering to our forefathers.

Money to spend in the spiritual world.

In the past, these ceremonies would take place in three different locations because the early settlers from China, talking about the railway workers, they were buried in three different cemeteries.

>> Dad left his village in the province of Guangdong, China, and boarded the Empress of Asia headed for Vancouver.

He was only 13 years old.

He then made his way to Montreal where, like the rest of the country, Chinese were not welcomed with open arms.

The Montreal Star reported that men known as Chinese trackers hunted any man who tried to escape deportation back to China.

Chinese men being shipped to other destinations via Montreal were locked up in the basement of Windsor Station that was known as the Chinese quarters.

And if the Chinese tried to escape their harsh reality by smoking opium, they risked being rounded up by the police.

In 1923, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King's government debated over the Chinese Immigration Act.

The act banned all Chinese immigration except for merchants, students and diplomats.

It came into law that year on Dominion Day, which is now known as Canada Day.

From that day on, the Chinese refer to it as Humiliation Day.

I was an adult when I finally understood that was the reason why my father never took part in July 1st celebrations.

To get a better sense of what my father's early life in Canada might have been like, I met with families of other restaurant owners to compare stories and share family history.

Jan and Julie's father, Bill Wong, ran several successful restaurants in Montreal, including one of the biggest that bore his name.

>> He had to go back.

It was the Depression.

1929, he had to go back 'cause there was not enough food to eat in Montreal.

So my grandfather sent them back because you imagine how bad it is in Montreal if they send them to China because it's better?

>> The year my father came back from China is in my book "Red China Blues," and the year he went to China is in there, too.

But I had to interview my dad to find out his life story.

He never talked about it.

And when I was interviewing him, he didn't want to talk about it.

I could get him for 10 minutes, and then he would get up and walk away because it was very painful.

His childhood was painful.

Having to go back to China -- Can you imagine growing up in Montreal and suddenly being sent to China for the first time in your life and having to take care of your mother and your baby brother and your baby sister and another baby on the way, and he had to farm the land.

So in a way, it was a horrible experience.

And so for me to extract it from him, I had to follow him around.

He'd get up, walk away.

He didn't want to talk about it, so I'd have to wait a little.

Then I'd have to grab him again because I needed to know for the chapter in my book about the family history.

But if I hadn't done that, and I think in many Chinese families, their history is a very unhappy history.

Our families, in a sense, were also separated because my father's younger brother was stuck back in China with his mother.

So the whole family was fragmented in those days.

>> And then I believe he came back because he was the eldest son.

And my grandfather was getting old, and my grandfather died a few years after he came back, and he needed his eldest son here to bury him.

But also when he was coming back from China, he was coming back on a ship.

They passed Japan.

The Japanese soldiers came on the ship.

They were going to take my father off, but a Canadian doctor was there and they said, "Don't touch him.

He's Canadian."

>> Yeah, the ship doctor, C.P.

Shipps, saved him.

>> So the Canadian doctor saved my father's life.

>> 'Cause he was Canadian, but he couldn't speak English.

>> Yeah.

>> Japan was at war with China then.

>> That's why he left.

He left China because Japan was starting to invade China.

So he came back, and the ship that took him stopped at a port in Japan.

They tried to take him off because they thought he was a Chinese national.

Because he looks Chinese.

>> They were putting them in concentration camps to work.

>> He would have died.

>> Yeah.

>> He would not have survived.

>> May Wong, who is no relation to Bill Wong's family, described how the Chinese Exclusion Act affected her parents in her book "A Cowherd in Paradise."

Considering that the Chinese population in Montreal was quite small at the time, we think our fathers must have known each other.

I contacted her at her home in Victoria, British Columbia.

>> My father, Guey Dang Wang, came from China to Canada in 1921.

He was about 19 years old, and in fact, he spent his 19th birthday waiting to pay his $500 head tax.

He was waiting in an immigration building that was reserved for the Asiatic steerage passengers on the Empress of Japan.

And this was called the pig pen.

So my father came to Montreal during the time of the Great Depression.

He actually didn't have very much choice in the matter as he was sent a one-way train ticket from a benefactor who lived in Montreal and owned a laundry there.

Well, he chose the restaurant business because that was the kind of work that he knew about.

He had also worked in the Chinatown restaurants, and that's where he met a couple of members of the Tang family, and their names were Jasper and Gordon, and the three of them formed a partnership.

Well, they decided to go to downtown Montreal and not to Chinatown because I think they felt that there would be more opportunities to attract different kinds of customers.

>> After my father passed away, we discovered this photograph among his possessions.

My father never gave any indication that he had enlisted in the Army during the Second World War.

So why was he in uniform?

It turns out he was one of 54 Chinese men and women who volunteered with the Civil Defense League in 1942 to protect the city of Montreal from the German Reich and other Axis Powers.

This certificate, dated June 1, 1945, thanking him for his services, was signed by the same Prime Minister who had passed the Chinese Exclusion Act.

The Chinese community celebrated the end of the war.

After lobbying by the Chinese community and its supporters, the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1947.

Chinese men were finally allowed to become citizens and bring their wives and children to Canada.

After having been separated for over a decade, my parents were finally reunited.

My mother, Wei Yuk Sim, arrived in Canada in December 1950.

Her one-way ticket from Hong Kong to Montreal cost almost $1,000.

My father borrowed money to open the restaurant from the Lee Association, which is one of many family associations where all the members have the same surnames.

In the past, the Family Association provided housing by renting small rooms to the men.

They also helped them maintain contact with their families in China, provided support for new arrivals, and shipped the bones of the deceased back to China for burial in the ancestral plot.

Nowadays, the association operates mainly as a social club.

One old timer told me that on Saturday nights, La Gauchetière Street was completely lined with cars.

Chinatown's restaurant and its nightclub were popular with Montrealers.

But instead of opening in Chinatown, my father, along with three partners, opened Lee's Garden on Park Avenue in 1951.

>> Daddy always worked the night shift.

This was a 12-hour shift that started around 6:00 at night until 6:00 in the morning the next day.

So he would get up, get dressed, and he was always really well groomed.

He'd put on a tie, a three-piece suit, and he would put pomade in his hair to keep it all in place.

And he always wore beautifully polished leather brogues.

On the same block of buildings where the restaurant was located at 1240 Stanley Street were a number of cabarets, strip clubs, and nightclubs, and these were open 24/7.

Sometimes people would refuse to pay after a meal.

Daddy wouldn't let them.

I called him the enforcer because he owned a pair of metal knuckle dusters and a billy club.

And if people still refused to pay, he wouldn't hesitate to fight them.

Sometimes he'd have to call the police, and then after his shift was over, he'd have to go to small claims court.

He believed in fighting for justice.

>> So he opened the House of Wong on Queen Mary, and he was instantly busy.

>> It was such a huge risk to move out of the safe confines of Chinatown.

There was no physical danger to a Chinese restaurant moving out of Chinatown.

But the danger was, would it work?

Could you run a restaurant that catered strictly to non-Chinese?

Because if you stayed in Chinatown, you would have some Chinese customers and some non-Chinese.

And so the risk was a business risk.

>> So tell me the story of how he decided to open a Chinese buffet.

>> Pascal Realty -- Remember Pascal Hardware?

>> Yes.

>> They approached him because, of course, that's the community.

And they said "We have a building on Décarie," which was the outskirts of Montreal at that time.

So anyways, they offered it to my father, and that's -- he took over the building.

And at the beginning, it was very hard on him.

He said "I couldn't fill up the dining room.

I had to put these Chinese dividers to make it feel more intimate."

And he tried many different models.

>> So anyway, I'm trying to time it to the cousin's wedding.

Why?

Because at the rehearsal dinner in Toronto, we went to a restaurant called The Town and Country, and it was an all-you-can-eat roast beef buffet.

And a light bulb went off in my father's head and he suddenly thought, "We can do this for Chinese food."

So it had to be about that time.

He had partners, minority partners.

And they didn't agree.

They said, "We'll go bankrupt.

People will eat -- How can we make any money this way?"

And I guess Dad said, "Let's do it."

Uh, he was very forceful, and so he decided to do it.

And it was amazing.

Instantly popular because Chinese food is made for big families to eat.

Nobody eats one dish.

They always share.

But in the Western countries, nobody goes out with 10 people to eat.

They go out with two people.

So how can two people eat properly, Chinese style, and have a little bit of each?

The answer was the Chinese buffet, and that was his genius.

He figured it out, and he he took the risk.

You know, you have to buy all those, like, stainless-steel tables.

You have to convert your menu.

Is it going to work?

And it worked because people loved it.

You could eat as much as you wanted.

And they didn't -- They didn't go bankrupt.

They made a -- They made a ton of money.

>> Why downtown Montreal and not Chinatown?

Well, unfortunately, I didn't have enough time to ask my father the questions about what some of the barriers were for him in opening up in downtown Montreal.

As you know, the restaurants and stores down in Chinatown were there because there was a community there and there was a support network.

And so opening up a place in downtown Montreal where there were no other Chinese businesses would have been a bold move on their part, I'd probably say.

The restaurant, I think, attracted quite a number of different customers, including Jewish customers.

In fact, I saw an ad in the Canadian Jewish Review that said that China Garden Cafe was a very convenient place for ladies to meet their friends after shopping.

>> Chinese food has woven its way into the fabric of Jewish life.

Don't know why.

I don't know where.

But there's an old Jewish joke that goes that if a Catholic person is having a crisis of conscience, they will go to church.

If a Jewish person is having a crisis of conscience, they will go for Chinese food.

>> Many Jewish people, including myself, were raised on traditional Jewish foods.

And as we got a little older as teenagers, we wanted something different, but we weren't used to food that was radically different.

Though the Chinese food fit the bill because it was a little different.

We could claim that it was a little more exotic.

♪ >> I think automatically when we think about Jewish food and Chinese food, we might not see the resemblance.

But when you actually look at it, there is some -- there are some interesting overlaps.

One of them is that according to the kosher food laws, you can't mix milk or dairy and meat.

And in Chinese food, there happens to not be much use of dairy.

So there's that parallel.

Also in terms of flavorings, there's a lot of sweet and sour flavorings used in both of these, in Canadian Chinese cuisine and in Eastern European Jewish cuisine.

So despite seeming like they're very, very different cuisines, there are some interesting similarities between them.

>> In another lifetime, much earlier than this one, so to speak, I was the owner of Ruby Foo's Restaurant in Montreal.

The Chinese food was certainly not kosher, and that was never in view.

It happened that we were Jewish, but we had no intention of having a kosher Chinese restaurant.

That was something for our private lives, not something for our business lives.

>> We didn't think of it as pork because generally it was -- it came with heavy sauces.

>> The basic concept for our family and a lot of other secular families was if you're eating Chinese food and something is hidden inside, inside a noodle like a won ton dumpling or egg rolls, if you can't see it, you don't know what you're eating.

So you just don't think about it.

You forget about it.

>> There's been a term that's been created within academia and among food scholars called "safe treyf," and Chinese food was safe treyf.

So what we mean by this is that even though there would have been shrimp and pork in the food, it was chopped up so that you couldn't really tell exactly what you're eating.

>> Tell me why your father decided to open a Chinese restaurant.

>> He came into possession of a building that was a restaurant that was bankrupt.

And he was wondering what to do with this building.

And so he decided he was going to open a restaurant.

It became a Chinese restaurant because he found a Chinese chef.

And so it opened in May of 1945, just as the Second World War was ending.

Well, Ruby Foo is the name of a Chinese woman living in New York, and she had two or three restaurants.

There was certainly one in New York, one in Boston, I think, and one in Washington.

And he approached her and asked if he could use the name.

Well, it was unique in a couple of respects.

It was, A, much more expensive than all the other Chinese restaurants.

A different level of restaurant, so to speak.

Secondly, it was in a very different place.

It was on Décarie Boulevard, whereas all the other Chinese restaurants in town were in what we call Chinatown now, and there were quite a few of them there for sure.

We weren't the first Chinese restaurant in town or anything like that.

And so Ruby Foo's became a kind of destination.

>> Can you tell me about the Chinese staff that you had?

>> At one time, we literally imported staff.

That is, we arranged to bring young men from Hong Kong.

Always young men, never women.

And they came to the restaurant to be -- mainly to be busboys, to help the waiters.

And then if they turned out to be valuable, as they often did, they became waiters over time.

It was a kind of career progression, if you can think about it that way.

Because we felt that having Chinese staff in the dining room gave the place a more interesting environment than having white staff.

In terms of the dishes that the restaurant was famous for, it's hard to know.

What I can really say is I can tell you what the dishes were that were most popular.

On the Chinese side, it was the lobster Cantonese, which we just couldn't get enough fresh lobsters in to satisfy the demand for it.

>> I think that the egg rolls at the China Garden Cafe were the best I have ever had, and they were even better than the ones that my mother made.

And she was a fantastic cook.

It had a cinnamon or a spice flavor that I've never been able to see in any other egg roll that I've tasted.

>> Egg rolls.

People would come on their way to Toronto -- They were ex-Montrealers -- They would stop at the restaurant and order a few dozen to freeze in Toronto.

>> They were rolled, they weren't folded, so they were rolled and cut so the edges would be black, charred black.

They didn't taste burned.

They tasted delicious.

But you got maximum stuffing and minimal pastry.

So people love the egg rolls.

Plus they could be cut into different sizes, so you could have cocktail size.

But that was the innovation.

They looked like a tube.

>> Judie, do you remember when you told me about how your parents met at Lee's Garden?

>> Yeah, that's where all the Jewish people hung out.

All their friends from Baron Byng, that's where they met, they went after school.

After sports events, that's where they went for their Chinese chow mein buns.

>> Oh, yeah, the Lee's Garden famous chow mein bun.

We had that at least once or twice a month.

The chow mein buns, from what I remember when we first started going there, were 25 cents each.

>> 25 cents then was a lot of money.

And so we usually took that 25 cents out of our allowance.

Maybe we had 75 cents as allowance.

And we would go in, and the big thing was to order a chow mein bun.

And when my kids asked me, "What's a chow mein bun?"

I said, "Are you kidding?"

It was a hamburger bun, and then there was the chow mein, and there was that brown, yellow kind of sauce, top of the bun, and then the sauce on top of it.

And we knew that we couldn't -- We wanted to stay as long as possible.

You know, there was a lot of flirting going on, a lot of checking out the other, the guys and whatever.

So you had to figure out ways to make this chow mein bun last as long as possible.

>> My father told me he invented the chow mein bun.

Well, it turns out that it was invented in Massachusetts in the 1930s or 1940s.

I imagine my dad actually came upon the recipe through word of mouth.

Strangely enough, although it was a popular dish, I've never tasted it.

This, I think, is as good a time as any to try it.

♪ So we're going to have a taste test.

And I'm sitting here with Susan, the owner of the Wok Cafe, and we're going to try it.

And we both realized that neither of us like chow mein.

So this is going to be a very interesting taste test.

So this is a chicken chow mein bun, and it has brown gravy on top and the crispy noodles are inside, and there's the vegetables as you would get chow mein.

I like the noodles, so I'm going to take the noodles.

I like it.

I think it's because I like the crunchy noodles.

>> I like the gravy.

>> You like the gravy on it?

So I think we have a winner, and we both like it.

So now the real taste test comes, and we're going to ask some of the customers of the Wok Cafe to try it and tell us what they think.

>> I love chow mein.

And I love the -- You can taste the flavor of the chow mein for sure, even through the bread.

It's very different, you know?

>> It's absolutely delicious.

It has a little bit of a crunch to it.

The chicken is nice and sweet.

It has a very, very nice taste.

>> Thumbs up.

>> Eating another culture's food is a way to get to know another culture.

And even if both communities weren't interacting on a daily basis, necessarily or outside of restaurants, because of the fact that they were meeting in the restaurants allowed, well, the two communities to develop a bond that may not have happened otherwise.

This bond between them may not have been articulated or discussed necessarily.

But the fact that the the Chinese community was welcoming to the Jewish community, it was an important act to be able to go into these restaurants and feel welcome and feel like they could spend time there and socialize there.

In the early 1900s, the Jewish community and the Chinese community were both immigrated to North America in very large numbers.

They were two of the largest immigrant communities coming to North America.

I guess there were similarities between them in that they were the other.

They were both the other at that time.

The Chinese restaurants were actually a place where Jews could go and eel welcome, feel like it was a safe place for them to be.

The other big reason as to why Jews were going to Chinese restaurants was -- So in the '50s is when many in the Jewish community are becoming more economically well established and moving up into the middle class.

And at that time, going out to eat was a signal of one's belonging to the middle class.

>> The Chinese Canadian restaurant is more than just a place to eat.

It embodies history and stories that are waiting to be told.

Karen Tam created an installation known as Gold Mountain Restaurant that examines and celebrates the humble eatery.

>> The name of my family's restaurant was called Restaurant Aux Sept Bonheurs.

I started thinking about why many of my friends' families, my parents' friends, why everyone was in the restaurant business.

For the Gold Mountain Restaurant, I wanted to do installations because it was a way of engaging with an audience in a way that I felt a painting or a photograph don't.

For example, in my spaces like the dining area, people are welcome to sit down.

They sit down, watch the videos, push through the doors.

And in that way, that kind of engages.

It's like a corporeal experience.

Then it kind of makes you think about your past, your memories, your engagements, your connections, I guess, of your local Chinese restaurant.

The type of restaurant that I was interested in depicting in a way that I wanted to speak about were these old-style Chinese Canadian, not not the ones that are termed "more authentic."

And they were very similar.

I mean, everyone's from a Hoisanese background serving very similar types of food.

The customer, the clientele were mostly Caucasian Canadians because they were in communities that were mostly white.

And so they had to adapt, I believe, not just the cuisine, but the decor.

So it's exotic but not too exotic.

Exotic enough.

Just familiar.

Sometimes, you know, the owners, they're families who usually don't come to an art gallery, they'll come because it's in a way paying homage to their experiences and saying, like, the Chinese restaurant, why shouldn't it be in the space of a museum or a gallery?

It's more about talking about the experience and highlighting the work, the lives of restaurateurs and their families, as well as, overall, the immigrant, the history of Chinese immigration to Canada.

And there was, still is, a lot of difficulties and hardships that people face, including racism.

I guess just having people think about, the next time they go to a Chinese restaurant or an ethnic restaurant, to think about not just the food that arrives, but the lives behind the counter, behind the doors.

>> In going to eat the food of another culture, whether it's at a restaurant or at someone's home, it shows an openness to learning about another culture, to being open to the people of that culture.

And I think that, you know, nowadays with all this, there's a fear of other cultures that's happening, you know, these days around the world.

And I think going to a restaurant can actually be a very powerful thing because you actually get to know the people of that culture in a very tangible way.

>> In 2014, many in the Chinese community were offended by a commercial that showed a Chinese restaurant.

I didn't understand why people were upset.

I'm proud of my family's restaurant.

It's a part of my identity.

To get a better idea of both sides of the argument, I spoke with two people.

Cathy Wong started a protest in Montreal that spread across Canada.

Wong ran for municipal elections in 2017 and won her running, becoming the first Asian woman to be elected in Montreal.

Then Montreal Mayor Valérie Plante named Wong as speaker of the Montreal City Council, the first woman to ever hold that position and to the executive committee.

And Henry Kwok, the actor in the commercial.

>> Well, I was really surprised by it.

I didn't see it coming at all.

And as it started to unfold, I kept looking at the newspaper articles and the TV interviews to see specifically what it was that people were upset about.

And the stuff that I got made me think, "Well, I don't think anybody really has an idea, anything specific that they can say at this point."

There was another comment that was made that went something to the effect of "This commercial makes you uneasy and it makes it look racist without you knowing exactly why."

And I thought, "Well, that's not fair.

I mean, if you don't know what's offensive about it, if you don't know why you're offended, then how do you expect the people who made the commercials to understand what's offensive about it?"

>> Well, first of all, I think that it's just a missed opportunity to show the Chinese community as it is today, a contemporary Chinese community.

I just thought it was really sad that we had to go back to those stereotypes, to those clichés that were constantly used.

>> Actually, when I went in to do the audition for the role, you know, I did my first take, and I did it the way that I -- pretty much the way I did it on the commercial.

And the the director was like, "Okay, that was good.

But we really are going for some realism here, so we want to see what it would look like if you were really angry."

And I told him, I said, "Well, this is a commercial.

You don't want to see me authentically express anger because it's going to scare everybody when they're watching this commercial.

This is a comedic piece.

You want comedic anger.

You don't want real anger."

But I said, "I'll do it for you and you can see what you think."

So I did.

I acted like I was really angry, really mad.

And he said, "Yeah, yeah, that's too much."

So that's how we ended up backing it up and we ended up moving it to what we actually did.

>> I know that there are big challenges when it comes to having roles when we're a visible minority in Quebec television or even in movies or in theaters.

So there are challenges.

And I can totally understand that when you're an actor and you're looking for roles that you have to unfortunately accept those type of roles.

So I don't want to put the blame on the actor.

>> I think that you could argue that it was a stereotype, you know, but I don't necessarily think that it has any kind of negative comments to make about the Chinese in general.

I think it's very typical that Chinese people own Chinese restaurants.

There have been people in my family that owned Chinese restaurants.

My father worked in a Chinese restaurant when we first came to Canada.

So, yeah, okay, you can call it stereotype, but I don't see where the offensive or the insulting part of it is.

>> There's such a big diversity of Chinese restaurants today everywhere in the world, not only in Montreal.

In fusion with other types of recipes like, for example, they're creating General Tso poutine, and they are offering ceviche and salmon teriyaki, you know, and they're mixing up and they're creating fusion between different types of recipes.

And when you go inside, you don't find that cliche, stereotypical type of restaurants where you would see contemporary music and even contemporary Chinese music, which doesn't sound like "ding, ding, ding."

I remember the media is even wanting to invite a Saint Hubert Representative and a Chinese person to debate live on the radio, which they refused to do.

So we accepted the invitation.

So we were there to express our point of view.

But Saint Hubert wasn't there to actually express their side of the story, so we never really got to exchange on that matter.

They did write us back online and there was a debate mostly online.

>> So now, you know, a few years later after this commercial was shot, we now have shows like "Kim's Convenience" where, yeah, that's very stereotypical, but I don't think anybody looks at it as being an insult to the Korean people and an insult to Asians or anything like that.

It's a job that they do.

It's a job that they do for historical reasons.

But I mean, this is what their authentic life looks like.

>> I didn't go there on a date, but I can tell you one time that sticks out in my mind.

Like my heart just goes pitter patter just thinking about it now.

I had a boyfriend who moved away.

He lived in Montreal, and then he moved away.

And I was heartbroken that he moved away, but he was gone.

And I used to think about him, but that was it.

And I remember one day sitting with my friends in Lee's Garden at a booth.

And in he walked.

And I remember how -- you know what it feels like when you haven't seen someone that at 14 or 15 you feel you're madly in love with?

And then to see him again.

I will always associate that little love thing with Lee's Garden.

>> After running the restaurant for over 20 years, my father decided to retire.

The new owner decided to make a few changes.

>> Someone came in and offered to buy us out of the clear blue sky, and we asked how much they were offering.

They mentioned a price that we thought was far more than the place was worth, and we sold it.

>> There was a boycott.

This is the article I did about the shooting at Dawson College, and I got a lot of hate e-mails, very racist stuff.

And so as part of that attack on me, they called for a boycott of the family restaurant.

And there were many cartoons, many racist cartoons.

And it was a really difficult time.

And I think the business was affected by it because it was soon after that -- that's right, it was soon after that that our brother closed it, because he was still running it.

Our father had stepped away.

And I think that was a big factor in it.

It was very hard because our father felt so bad about it.

But, you know, a restaurant doesn't have things in it.

It's just the tables and the chairs.

The restaurant is really the vision of the founder, the owner.

It's the people in the restaurant that create it.

It's not the building and the tables.

So, you know, when it closed, it really was gone.

>> The restaurant closed for good in November 1986, and that was when the partnership was dissolved.

But my father had already been retired for eight years, and he had decided at the age of 76 that he had worked long enough.

My father never wanted any of us to work in the restaurant.

He thought it was too difficult a job.

And as the enforcer, he saw a darker side of human life.

He saw that people could take advantage of him.

And so he wanted all of us to have an education and do something else so that we would have a better life than he did.

>> I wonder if my father was scared crossing the ocean alone.

The survival of his family in China rested on his small shoulders.

He landed here not knowing the language.

Yet he persevered.

He created a life where he could raise a family for which I will always be grateful.

I once asked if he had always wanted to own a restaurant.

He said no.

He wanted to make something with his hands like a carpenter.

But he didn't have much choice.

He may not have created something you can hold in your hands, but he created something people can hold in their hearts.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ And I will always be the daughter of the owner of Lee's Garden.

♪ ♪ [ Bell rings ] ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪

Meet and Eat at Lee's Garden is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television