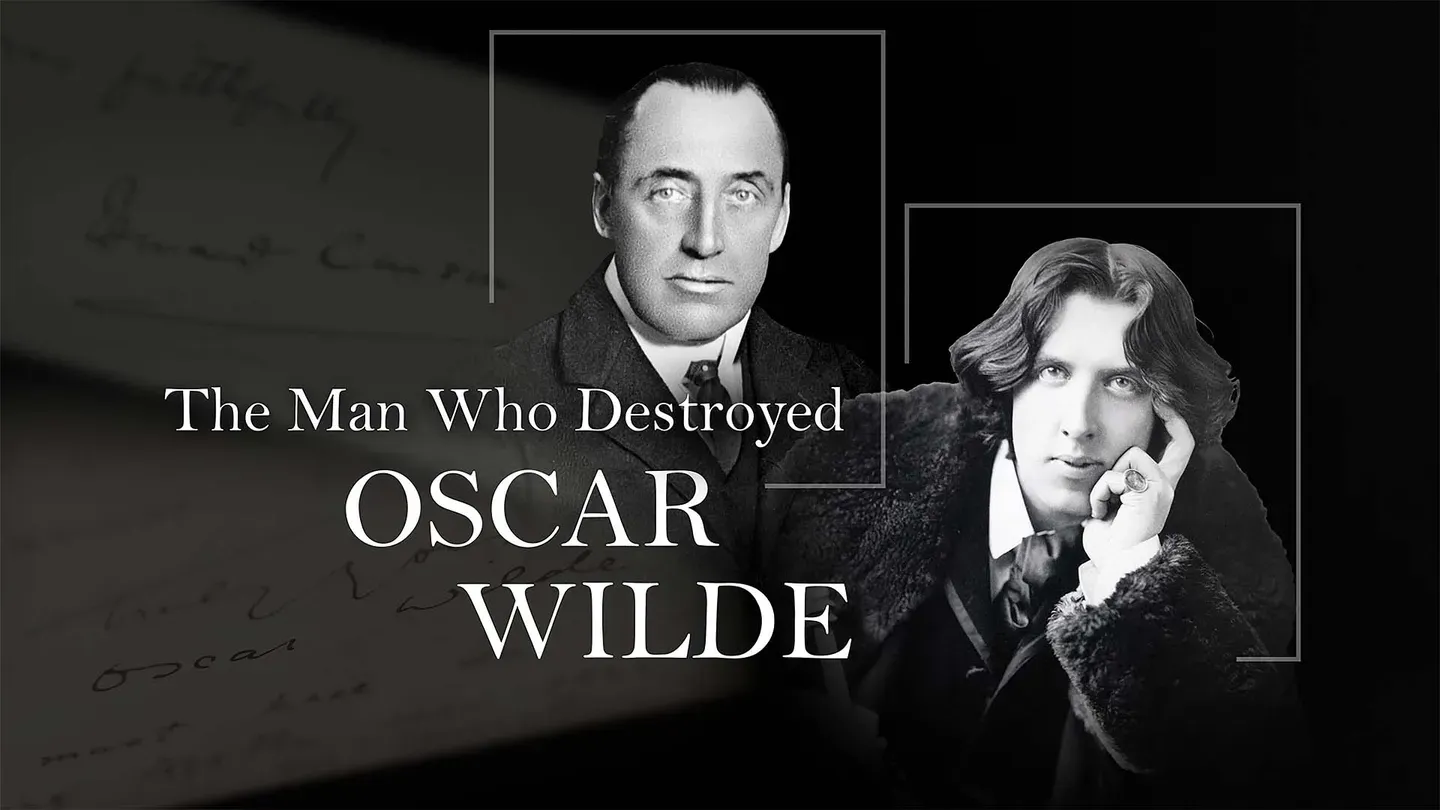

The Man Who Destroyed Oscar Wilde

Special | 50m 12sVideo has Closed Captions

Merlin Holland, grandson of Oscar Wilde, tells the story of the playwright’s downfall.

Merlin Holland, grandson of Oscar Wilde, tells the epic story of the famous playwright’s downfall at the hands of the man who he once called an "old friend." In 1895 Oscar Wilde fought a spectacular duel in court with Edward Carson, an up-and-coming lawyer and politician. It was one of the most scandalous trials of the Victorian era. It led to Wilde’s ruin and imprisonment for homosexuality.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

The Man Who Destroyed Oscar Wilde is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television

The Man Who Destroyed Oscar Wilde

Special | 50m 12sVideo has Closed Captions

Merlin Holland, grandson of Oscar Wilde, tells the epic story of the famous playwright’s downfall at the hands of the man who he once called an "old friend." In 1895 Oscar Wilde fought a spectacular duel in court with Edward Carson, an up-and-coming lawyer and politician. It was one of the most scandalous trials of the Victorian era. It led to Wilde’s ruin and imprisonment for homosexuality.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch The Man Who Destroyed Oscar Wilde

The Man Who Destroyed Oscar Wilde is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

(bright music) I can remember my parents saying to me, my mother particularly, "If anybody asks you, 'Are you the grandson of Oscar Wilde,' you just say yes and conveniently change the subject."

Carson once was famous, and Oscar was once notorious and is now celebrated.

(Simon Callow) He knew how brilliant Carson was.

He was a notoriously brilliant, indefatigable, unrelenting cross-examiner.

I mean, he was just a star.

A great, great star.

(Gyles) Oscar Wilde was spinning like a top, and there's success in there, the words are coming out of him, there's a whirlwind of it, he's passionately in love, and he's now middle age, it's like a midlife crisis, he's fallen in love with somebody half his age, it's a boy who is incredibly beautiful.

It's so exciting, he is admired, and this top, the top spins, and it spins off its axis, and then the whole thing collapses.

He has all the frailties of a man and genius thrown in, and he crucified himself willingly to gain immortality, so for me, he's very much a Christ figure.

(Wilde's grandson) When Wilde found out that Carson was going to be defending Lord Queensberry, he's supposed to have said, "No doubt he will perform his task with all the added bitterness of an old friend."

Everyone thinks of Edward Carson as the man who prosecuted Oscar Wilde in the famous Queensberry libel trial of 1895.

In fact, he didn't prosecute him at all.

He simply subjected him to a cross-examination which was so fierce that it looked as if Oscar Wilde was in the dock rather than in the witness box.

But there were connections between Edward Carson and Oscar Wilde which went, apparently, back to childhood, and that's what I'm here to try and find out: something of the connections between these two remarkable men whose parallel lives seem to mirror each other.

(mellow music) ♪ In 1895, my grandfather, Oscar Wilde, fought an epic duel in court with a lawyer who he'd once called an old friend.

That lawyer was Edward Carson, and the case was one of the most scandalous trials of Victorian times.

It ended with Wilde's ruin and led to his prosecution and imprisonment for homosexuality.

But does Edward Carson really deserve his reputation as the man who destroyed Oscar Wilde?

♪ Well, it's good to be back in Belfast after a very long absence.

My last visit was 25 years ago when the city was a very different place.

See it very much more animated now than my first visit to St. Anne's Cathedral where the tomb of Edward Carson is, the only man to be buried here, I believe, and accredited with the downfall, in part, of my--my grandpa.

So, a slightly emotional moment, I suppose.

(bright music) ♪ What I find fascinating is that there is just his surname, nothing else.

Carson.

And like Oscar in later life when he said, "I shall soon be known as the Oscar or the Wilde," if you mention Carson today or Wilde, you know exactly who you mean.

He must, just with his surname here, have been incredibly revered and loved by the people of Ulster.

Certainly by the unionist population in Ulster, he has name recognition through his surname alone, Carson.

This, I think, is part of a wider reverence that he's given during his lifetime.

In 1912, 1914, at the peak of the Home Rule Crisis, Carson assumes an almost saint-like status within the unionist north of Ireland.

At that stage, people want to touch him and they want to be identified with this kind of minor deity.

And yes, he's Carson, he's Carson.

Not Sir Edward Carson.

He's Carson.

But he spends most of his later career in England, and when he dies, he's brought back to Belfast to be buried here.

(announcer) HMS Broke draws into Donegall Quay, a naval escort for Ulster's greatest son.

He lies shrouded by Union Jack at the stern, the flag at half mast.

Lord Carson, champion of her integrity, leader of her patriotic revolt.

In St. Anne's Cathedral, Belfast, he is to be buried.

(mellow music) ♪ (Merlin) Oscar Wilde and Edward Carson were both born in 1854 into affluent Irish-Protestant families in Dublin.

They grew up as privileged sons of the Ascendancy class and were almost exact contemporaries.

♪ It was here in Trinity College, Dublin, the Protestant university of the city, that Edward Carson and Oscar Wilde met again.

It was said that they'd been friends in their childhood, playing together on the beach, but then they'd gone to separate schools.

Edward Carson had gone to Portarlington and Oscar Wilde to Portora in County Fermanagh.

It was said that Oscar Wilde walked round the quadrangles of Trinity with Edward Carson, Edward Carson's arm around his neck.

Edward Carson later refuted this.

Perfectly understandably, they had gone in entirely separate directions.

Oscar, the aesthete, and Edward Carson, the legal man.

Whether or not the story is true is unverifiable.

Oscar left very little in the way of letters and documentation from his time here at Trinity, but it's a nice thought that they were once undergraduate friends.

(gentle music) ♪ "Better run up to Oxford, Oscar," said his old tutor, John Mahaffy, at Trinity College, Dublin.

Not quite clever enough for us here.

And so this is where he came, Magdalen College, Oxford, and where my father wanted to come five years after Oscar's death, and his family said, "No, you've got to go to Cambridge, we don't want any more connection with the dreadful Oscar Wilde," and where I came back in the 1960s.

I suppose I was sort of fulfilling one of my father's wishes which he couldn't have had back at the beginning of the century.

And then where Lucian, my own son, came, and Lucian then emulated his great-grandfather's success and got a double first in classics.

Genetic hardwiring, I suppose.

I think it embarrassed him slightly, almost.

(chuckles) But he deserved it.

♪ I think Oscar must be smiling on us today.

In this early morning light, Magdalen College never looks more beautiful.

He wrote about it quite movingly in that long letter from prison, "De Profundis."

"I remember when I was at Oxford saying to one of my friends as we were strolling around Magdalen's narrow bird-haunted walks one morning in the June before I took my degree, that I wanted to eat of the fruit of all the trees in the garden of the world, that I was going out into the world with that passion in my soul.

And so, indeed, I went out, and so I lived.

My only mistake was that I confined myself so exclusively to the trees of what seemed to me the sun-gilt side of the garden, and shunned the other for its shadow and its gloom...

I don't regret for a single moment having lived for pleasure.

I did it to the full, as one should do everything to the full.

There was no pleasure I did not experience.

I threw the pearl of my soul into a cup of wine.

I went down the primrose path to the sound of flutes.

I lived on honeycomb.

But to have continued the same life would have been wrong because it would have been limiting.

I had to pass on.

The other half of the garden had its secrets for me also."

It was here at Oxford that Oscar said the first thing he did was to lose his Irish accent, but it was also here that he started to become outrageous.

He decorated his rooms with blue china and peacock feathers, apparently, and one of his first positively outrageous remarks was to say that he was finding it harder and harder every day to live up to his blue china, a remark which was preached against in the university church by the university chaplain.

And it was from that moment, really, that Oscar Wilde's reputation as an aesthete and somebody who was going to tweak the nose of the British establishment really started here in Oxford.

(mellow music) Wilde and Carson both excelled in their chosen careers.

By the early 1890s, Wilde's star status in London as a playwright and aesthete was firmly established.

In 1892, Carson had also arrived when he was elected as an Irish Unionist MP.

He soon had a growing reputation in London both as a leading lawyer and an upcoming politician with powerful friends in the Conservative Party.

♪ I think I'm right in saying that you have, uh, some quite strong feelings about Oscar's double life and particularly as he portrays it in the plays.

It is a great Victorian theme, the double life.

They seemed to be obsessed by the idea of two sides of the same person and of secrets.

It is evident, almost from the beginning, anyway, at least the mature plays, everybody's hiding something.

(Merlin) CRIM 1, stroke 41, stroke 6, part 1.

A cold administrative reference to something which I think is probably one of the most extraordinary documents in British literary history.

The safe room.

It's obviously regarded by the Public Record Office as something pretty exceptional as well.

And inside is the famous card which the Marquess of Queensberry left at Oscar's club shortly after the opening of "The Importance of Being Earnest" in 1895, accusing him of being a sodomite.

(soft music) Well, my grandfather met "Bosie" Douglas, the young Lord Alfred Douglas, in 1891.

He'd just published "The Picture of Dorian Gray" which had generated untold column inches of vituperation in the press on the part of the critics about its homosexual undertones.

And before too long after this fateful meeting, Oscar and Bosie became lovers.

This enraged young Douglas's father, Lord Queensberry, who made every possible attempt to separate them.

(solemn music) (Neil) "Gay" is a 20th-century concept.

We're talking about the 19th century and we're talking about the words for sex between men was "sodomy" and the name for men who had sex with men was "sodomites."

Well, Alfred Douglas was a famous beauty.

It's one of those things that's a little bit hard for us to know.

You look at the photographs and you see a rather-- rather sort of a Greyhound-like figure.

Very, very slim and rather tight-lipped, and it's very hard to see the beauty that his contemporaries spoke of, but obviously he's a sort of beau idéal for Wilde both in terms of his looks and his electric personality but also because he was the son of a marquess.

(Rupert) It was a relationship about snobbery, really, from Oscar's point of view.

I think for an Irish man who'd come to England and, within 20 days, changed everything about himself to suit the English, for him to meet the son of a marquess was more important, really, than we can possibly imagine.

You know, the aristocracy in those days were like saints, you know, or gods.

Bosie was just utterly obsessed.

I mean, his sexual appetite, as far as we can understand, was enormous, I think probably far in excess of Wilde's, and he set up these sort of orgiastic events, and he was familiar with the rent boys of London, as you know, he was a world expert on that.

And Wilde was suddenly plunged into a world where you can have anything you want, you know.

"Come with me, I'll show you."

He inducted him into a world of, as Wilde says, the "Arabian Nights."

(mellow music) (Merlin) Quite apart from that, Queensberry also believed that his eldest son, Viscount Drumlanrig, was having an affair with Lord Rosebery, the man whose private secretary he had been and who had now become the Prime Minister.

♪ (Owen) In whatever sort of a mind he had, mad or sane, Lord Queensberry believed that Lord Rosebery was the lover of his son, Viscount Drumlanrig.

To have one Uranian, sodomitic son may look like misfortune.

To have two looks like hereditary.

He called Lord Rosebery a "Jew nancy boy" and a "snob queer" and a "bloody bugger."

(Merlin) And in 1894, when Drumlanrig was out on a shooting party, he was killed by his own gun, and the fact remains that it was almost certainly suicide.

So, Queensberry had lost one son to what he saw as the evils of homosexuality, and here was another who was having a dalliance with Oscar Wilde.

And later that year, Queensberry went round to Oscar's house in Tite Street in London and threatened that if he ever saw him with his son again, he'd thrash him.

He said, "I don't accuse you of immoral conduct with my son, but you look it and you pose as it, which is just as bad."

He left matters for a while until the premiere of "The Importance of Being Earnest" the following year, and he tried to gain access to the theater with a bunch of rotting vegetables but was turned away and went off, as Oscar described him, "muttering like a monstrous ape."

And he left a card, this very card, at Oscar's club.

"For Oscar Wilde, posing as somdomite," misspelled in his fury.

Once the card had been shown to Bosie and he says, "Ah, finally, we've got my father," Oscar becomes the cat's-paw in this ridiculous family squabble.

-Yes, yes, yes.

-But what they do, which has always seemed to me to be a completely mad thing to do but it was due to Bosie, was to sue the marquess for not just plain libel but for criminal libel.

Were you convicted of it, you could finish up in prison.

That's, of course, exactly what Bosie wanted, to see his father in prison.

They'd all been planning it.

The family had been thinking of ways to suppress the marquess in one way or another, either put him in a lunatic asylum or put him in a prison.

(Merlin) Once the Marquess of Queensberry had been arrested, he was taken off to the Magistrates' Court where he and the hall-porter and Oscar made their depositions in front of the magistrate, simply recounting the facts as they had happened, the hall-porter explaining how he put this card into an envelope because he realized that it was a pretty serious accusation.

Queensberry's deposition is very simple indeed but quite significant.

"I have simply to say this, that I wrote the card with the intention of bringing matters to a head, having been unable to meet Mr. Oscar Wilde otherwise, and to save my son, and I abide by what I wrote.

Queensberry."

And that was the basis on which Lord Queensberry was taken to court for criminal libel and defended by Edward Carson.

(somber music) ♪ Oscar Wilde has been part of my life since really before I can remember anything.

Even as a child, in London, I knew about Oscar Wilde, this figure, and I knew he'd been involved in a trial, but I didn't know what the trial was really about.

But my father was interested in the trial because my father was also a barrister.

And so, my father not only would have told me about Oscar Wilde, but he would also have told me about Edward Carson.

Can you remember anything he told you, what his view of Edward Carson's cross-examination was?

(Gyles) Yes, he can: Brilliant.

What's fascinating about this, of course, is these are two great performers, and you can explain to me, I mean, everybody wants to know, why did Oscar Wilde let this happen to him?

Why did he pursue this matter?

It's the question I'd ask him in the afterlife if we meet and I'm not upstairs and he's not downstairs or vice versa.

(Rupert) He just had a big head and he couldn't imagine what was gonna happen.

He was drunk.

Drunk on success and drunk on...arrival.

You know, I think he was a great arriviste, and he'd arrived, in his own mind.

He's a big star, and he thinks the whole world is built around him.

This isn't, you know, he's not a particularly-- as Max Beerbohm said, he was a rather revolting, I think, person at that point.

He was friends of royalty.

He thought he could move with impunity and indeed said, "Don't worry, the working classes are behind me, to a boy."

This typical behavior of a deluded star, really.

He thought he was bigger than the system.

(mellow music) (Merlin) Wilde's sensational libel action against Lord Queensberry began on the 3rd of April, 1895, in what's probably the most famous courtroom in England, the Old Bailey.

Wilde, the Irish nationalist, matched from the witness box against his old friend, the staunchly unionist Carson.

♪ It was set to become one of the most famous trials in British history, and yet the true record of the real trial of Oscar Wilde didn't turn up until more than a century later.

♪ Well, I suppose this has to be one of the Holy Grails of Wilde studies, really.

I was preparing an exhibition with the British Library back in 2000.

It was the first exhibition that they'd had devoted to one person.

I have to say, they were slightly nervous about the possibility of the public not attending, but Oscar Wilde pulled them in.

And as we were preparing the exhibit, somebody came in with a plastic bag, and in the plastic bag was the transcript of the libel trial.

I think, rather like the Holy Grail, we knew that it had existed, but we'd always assumed that it had been destroyed, and here it was from an impeccable provenance.

So it was the words spoken in court and taken down in shorthand.

It's the nearest thing we've got to, I suppose, a recording of Oscar Wilde.

But he went into court, I think, rather like, um, writing a play in which he was the principal actor.

He wrote the prologue, and after that, he didn't know what the outcome was going to be.

(Simon) You can't really separate any of this from Wilde's own absolutely misplaced faith in his own capacity to win the day with charm and wit and eloquence.

You feel him coming into the courtroom with some confidence that he'll win everybody over.

(Merlin) But again, the danger, the danger of not quite knowing how it's all going to pan out but having this misplaced confidence -in his own abilities.

-Yes, yes.

It was part of his...style, his shtick, as you might say, that--to be rather lordly and, uh, somewhat dismissive of, um, what he thought was vulgarity and so on.

Unfortunately, in the courtroom, it only came across as arrogance, extraordinary arrogance.

Everything that a solicitor or your barrister would say to you today if you go to court, "For goodness' sake, don't do."

That's exactly right, and he's contemptuous, for example, of the ordinary people who don't understand what he's written.

Carson is pursuing exactly the opposite case, that is to say, doing everything to persuade those jurymen that he, Carson, who, let's face it, is actually, even at this stage, a relatively distinguished individual, a double QC-- Ireland and England-- a former Solicitor General of Ireland, an MP as well for Trinity College, Dublin.

This is no man of the people, but he's persuading that jury, effectively, that he is.

Carson himself had a very pronounced Dublin accent and took a great deal of trouble to make sure that he never lost it, and do you know why?

Because when they came up against him in the witness box, they'd think he was a Dublin idiot, and then he'd make minced meat of them.

At one point in the cross-examination, Edward Carson has, in his hands, a letter which Oscar has written to young Alfred Douglas, to Bosie, and in it, he quotes from it, he says, "It is a marvel that those red roseleaf lips of yours should be made no less for the music of song than for the madness of kissing."

And he says to Oscar Wilde, "Is that a beautiful phrase?"

And Oscar replies, "I think it is a beautiful phrase."

"A beautiful phrase?"

"Yes, a beautiful phrase."

"'Your slim gilt soul walks between passion and poetry.'

Yes?

Is that a beautiful phrase?"

"Not when you read it, Mr. Carson.

When I wrote it, it was beautiful.

You read it very badly."

Well, that's not the way to treat your cross-examiner in court, and I think you have this feeling that Oscar is being just too clever by half.

And Edward Carson gives as good as he gets.

"I do not profess to be an artist, Mr.

Wilde."

"Then do not read it to me.

And if you will allow me to say so, sometimes when I hear you giving evidence, I am glad I'm not."

Of course, his biggest mistake is to treat the whole process like...a play at the theater, and he tries to get in as many jokes as he possibly can, scoring off Edward Carson at every possible opportunity.

(gentle music) "Listen, sir, here is one of your 'Phrases and Philosophies for the Use of the Young': Wickedness is a myth invented by good people to account for the curious attractiveness of others.

Do you think that is true?"

"I rarely think anything I write is true."

♪ "Have you ever felt that feeling of adoring madly a beautiful male person many years younger than yourself?"

"I have never given adoration to anyone except myself."

And when Carson asks him whether he'd taken a young man back to the Savoy Hotel and plied him with whiskeys and sodas and then taken him to his room and got into bed with him, um, Carson, like a terrier, keeps asking the same question to him: "Did you give him whiskey and soda?"

"No, I can't remember."

"Did he come back to the hotel with you after?"

"No."

"For two small bottles of iced champagne?"

"I say he wasn't there."

"Was iced champagne a favorite drink of yours?"

"A favorite drink of mine?

Yes.

Yes, strongly against my doctor's orders."

"Never mind your doctor's orders, sir."

"I don't.

It has all the more flavor if you discard the doctor's orders."

Laughter in court.

But Carson is hammering away, Oscar's scoring his points, but... the worst is still to come.

At one point, Edward Carson starts onto the associations that Oscar had with the servants and the young rent boys that he'd consorted with, and a servant was serving them at dinner, and Edward Carson says to him, "Did he dine with you?"

And Oscar says, "Certainly not."

You know, "Can't imagine that that could have happened with the servant."

"You told me yourself--" "It's a different thing-- if it is people's duty to serve, it's their duty to serve, and if it's their pleasure to dine, it is their pleasure to dine and their privilege."

"You say not?"

"Certainly not."

"And did you ever kiss him?"

"Oh, no, never in my life.

He was a peculiarly plain boy."

Oh, God, honestly.

How he could have done it, he-- one joke too many, and he-- he talked himself into prison.

The only thing missing in this transcript is... (chuckling) ...and I'm sure the transcribers would never have bothered to put them in, was a sort of Pinterian, pregnant pause.

"He was a peculiarly plain boy."

I think it fell into Edward Carson's lap.

I don't--actually I don't think that he was planning to crucify Oscar at this point in the way he did.

There's a pause.

"He was what?"

"Uh, I said--I thought-- I just thought him unfortunately-- his appearance was so-- unfortunately was ugly-- I mean, I..." And it's more or less then all over.

(Simon) I mean, it's a very provocative question, you know, "Did you kiss him?"

It must have taken Wilde completely by surprise 'cause it's so direct.

"Did you kiss him?"

Not "Did you have amorous intentions towards him?

Did you--did you engage in--" It was no lawyer talk there.

(Merlin) And then, of course, the trial collapses at the moment when Edward Carson starts his speech for the defense, and it's quite clear that these young... male prostitutes are going to be brought on one after the other, and Edward Clarke advises Oscar to withdraw from the case.

It was said that Edward Clarke, Oscar's own barrister, when he withdrew from the prosecution, had made an agreement with Edward Carson that the matter, now that they had withdrawn the prosecution, should be taken no further.

But that agreement, if there ever was one, was not stuck to.

Queensberry's solicitors immediately sent off all their papers, their witness statements, to the Director of Public Prosecutions.

And that led to Oscar's arrest the same afternoon as his own libel trial against Queensberry was withdrawn.

(melancholy music) Carson had won a famous, career-making case, but he is reported to have said to his wife, "I have ruined the most brilliant man in London."

Oscar was soon to find himself in the dock charged with what the law termed "gross indecency."

However, the trial ended when the jury couldn't reach a verdict.

And then, a retrial was quickly scheduled.

I suppose one has to accept the fact that the government were determined to put away and make a spectacle of a scapegoat.

Otherwise, why would they have brought in the Solicitor General himself in order to prosecute the last trial against Oscar Wilde, a man who normally was only involved in cases of rape or murder or treason?

So, things were going on at a very high level.

The political implications of this case, as well as the literary ones, were undoubtedly extremely important.

♪ We don't know why, but before the retrial, Carson apparently tried to intercede on Wilde's behalf.

He went to the Solicitor General and said to him, "Can you not let up on the fellow now?

He has suffered a great deal."

But the reply was that the prosecution dare not drop the case for political reasons.

The main theory is that Queensberry blackmailed Rosebery and the Liberal government that if Oscar Wilde wasn't sent to prison, he would expose sodomy at the highest levels in British political life.

I've been looking for the smoking gun for years, a letter from Queensberry to Rosebery which says, "Nail the bastard or I'll spill the beans."

In this last trial, Wilde was found guilty.

On the 25th of May, 1895, he was sentenced to two years' hard labor.

The man who had once been the toast of London society had now become a despised and bankrupt criminal.

His downfall was complete.

(Simon) There was a great satisfaction, let's put it that way, in the establishment that this court jester who'd been tolerated for too long was finally being put away.

(Merlin) He was the perfect scapegoat.

He was a scapegoat for decadent literature, if one can call it that.

He was a scapegoat for the homosexuals who hadn't been prosecuted under this law until then.

He was the perfect example for the government to send to prison to show that they meant business.

Towards the end of Oscar's time in prison, he had petitioned the Home Secretary to be allowed to have pencil and paper in his cell and wrote a long letter to young Alfred Douglas, which has since become known as "De Profundis," "from the depths."

And at the beginning of the letter, he...says to Bosie, Alfred Douglas, "You never really understood my art.

You knew what my art was to me, the great primal note by which I had revealed, first myself to myself and then myself to the world, the real passion of my life, the love to which all other loves were as marsh water to red wine or the glowworm of the marsh to the magic mirror of the moon."

It's a most wonderful phrase.

And there's one phrase here which I think will probably put Edward Carson's shade to rest.

"I had genius, a distinguished name, high social standing, brilliancy, intellectual daring.

I made art a philosophy, and philosophy an art.

I altered the minds of men and the colors of things.

There was nothing I said or did that did not make people wonder."

I mean, the extraordinary arrogance of it, but I suppose one has to accept that, today, there is an element of truth in it.

And then comes the, I suppose, almost the explanation for his madness, the mad-- the sheer madness of taking Queensberry to court.

"I ceased to be lord over myself.

I was no longer the captain of my soul, and did not know it.

I allowed you to dominate me and your father to frighten me.

I ended in horrible disgrace."

And somewhere else, he says, "I staggered as an ox into the shambles."

Events have overcome him.

He's no longer in control of himself, and I think that he realizes this in prison.

(dreary music) After his time in prison, Wilde's health as well as his reputation was ruined.

His marriage to my grandmother, Constance, was over.

She left England with their two sons and changed our family name to Holland, and Oscar would never see his children again.

♪ I think I'm probably one of the few people in the world entitled to say that, "At times, Oscar exasperates me," and actually get away with it.

Um, exasperates, really, because of the misery he brought on his family, and my father and my uncle in particular, let alone my grandmother who died at the early age of, uh, 40, in 1898, less than a year after Oscar came out of prison.

(solemn music) Carson went on to enjoy a glittering career as the leader of unionism, architect of Irish partition, and father of Northern Ireland.

♪ When Carson started becoming the great popular leader of the Ulster Unionists, doing this fantastic business of raising an army, drilling it to be ready to commit treason, to fight the army of the United Kingdom, and the reaction of most people, especially in Ireland but, to a great extent, in Londoners, "Oh, he's posing."

The same word that Queensberry used, "Oscar Wilde posing as a sodomite."

Carson is posing as a military leader.

(dramatic brass music) ♪ (Merlin) And this statue was put up during his lifetime?

(Alvin) Well, I suppose that is slightly surprising, but there's no question that, whatever Carson's other qualities, he, uh, is remarkably sensitive about his reputation and there is a narcissistic quality to him.

(Merlin) Do you think, underneath it all, he was a modest man?

(Alvin) No, I think he needed an enormous quality or power of self-possession in order to perform in the courts.

What you see throughout his life and career are these periods of intense work followed by exhaustion, depression, and then recuperation.

Everything that you have just said could be applied to Oscar Wilde.

(mellow music) ♪ From 10 Wilton Street, London, SW1, 30th of June, 1950.

I suppose the biggest surprise of this visit to the Public Record Office in Northern Ireland is this letter from what is none other than my godfather, the 2nd Earl of Birkenhead, Freddy Birkenhead as I knew him, to Montgomery Hyde about his biography of Carson.

"Where I might be able to help is that I knew Carson personally very well.

I have no doubt that if I start thinking, I can recall some of the conversations, particularly in relation to the Oscar Wilde trial.

As you know, when Wilde was told he was going to be opposed by Carson, he thought this a great joke and went round telling all his friends, 'I'm going to be cross-examined by old Ned Carson.'"

And what is infuriating is that my father never told me that Freddy Birkenhead had known Montgomery Hyde and that he had known Edward Carson, because he lived after my father died and I could've gone and asked him more about Edward Carson and about Edward Carson's views of my grandfather and that disastrous trial.

But I suppose that's one of those things.

My father died too young, and there are so many questions I wanted to ask him.

(solemn music) ♪ When my grandfather was released from prison, he came straight over to France, and after a disastrous reunion with his young lover, Alfred Douglas, he finished up here in Paris.

And at this hotel, the Hôtel d'Alsace, 13 Rue des Beaux Arts, on the Left Bank, he spent most of the last four years of his life.

The proprietor was a wonderful man, Jean Dupoirier, who overlooked a lot of the bills that Oscar owed him and was extremely generous and kind to him.

It's amusing, I think, to look at the plaque on the side of the wall where they can not only get wrong the day of his birth but also the year, and I've told them many times about this, but it's now gone into history, so I suppose it has to stay as it is.

But it's, I think, significant in the whole story of Oscar that people get things wrong and then they become enshrined in fact, and it's very difficult to rub them out after that.

Well, it was just a short walk from Oscar's bohemian hotel here on the Left Bank of the Seine, across the river, and up to the Grands Boulevards where he'd sit and drink absinthe or cognac and hope that somebody was going to pay for a glass for him, but he knew that he'd have to come back across the Seine at night, back to his modest hotel, and the Seine sort of represented to me a division between his past life and his present life, past life being the grandeur of posh Paris and the present life being the modest life that he was living in a little hotel in the Rue des Beaux Arts.

(gentle music) ♪ Well, I'm here to see Father Troy at St. Joseph's Church in Paris where they keep the register in which was recorded Father Cuthbert Dunne's conversion of Oscar Wilde to Catholicism on his death bed.

I've never seen it before.

Um, I'm feeling a little bit apprehensive.

I think it could be quite a moving experience.

-Father Troy.

-Delighted to meet you.

(Merlin) I'm very delighted to meet you too.

-How are you?

-Very well indeed, thank you.

(Father Troy) This is 1863 to 1925.

Baptisms, confirmations, and conversions.

-Oh!

-So this is it.

So when we open this here, this is-- You read it because I'd love you to see this and you read this for the first time.

"Today, 29th of November... -1900..." -God.

It's very... very moving.

"Today, Oscar Wilde, lying in extremis at the Hôtel d'Alsace, 13 Rue des Beaux Arts, Paris, was conditionally baptized by me, Cuthbert Dunne.

He died the following day having received at my hands the Sacrament..." -Of Extreme Unction.

-"...of Extreme Unction," which, as you said, was what it was called in those days.

(Father Troy) In those days, it was called Extreme Unction because it was in extremis and he gave... And that would've been his, um, his full... And as I say, in another place, Father Cuthbert Dunne explains that he would have given him Holy Communion, which was Viaticum, but because he was in extremis, he didn't feel he was able for it.

(Merlin) To see Father Cuthbert Dunne's signature on the entry in the book, which he put there the day after he'd gone across the Seine to the Hôtel d'Alsace to give Extreme Unction to...Grandpa was just unbearably moving, and it's wonderful to think that Father Cuthbert was an Irishman like Oscar, and I think probably was totally unjudgmental.

(mellow music) ♪ This is the north transept of the Église de Saint-Germain-des-Prés on the south bank of the Seine where they brought Oscar's body on the 1st of December, 1900.

He died the day before, around 2:00 in the afternoon, and it was a short walk from his hotel, the Hôtel d'Alsace, to come here to this side entrance to the church.

It was the side entrance because they wanted to keep it as discreet as possible, and there were, apparently, 56 people who came, many of them unknown, five heavily veiled women.

Who they were, we still don't know.

Father Cuthbert Dunne, who had received him into the church two days before conducted a Low Mass, and from here, they went out to the suburbs, south suburbs of Paris, to Bagneux, where he was buried for the first time.

The first time because it was in 1909, uh, nine years later that his remains were finally transferred to Père Lachaise when there was enough money to buy a permanent plot.

(stately music) (announcer) The escort halts outside the cathedral and up the steps to his last rest, Lord Carson is bound.

♪ The mourners follow.

Lady Carson.

Supporting her, Lord Carson's two sons.

Wreaths and tears bespeak Ulster's grief for her hero.

Hero he was to the six counties of Northern Ireland.

♪ (solemn music) (Merlin) Full circle now, back to-- back to where I first met you.

(Rupert) Right, and how many years have gone past?

(Merlin) Well, it's five years now, I think, since the tomb was redone.

(Rupert) Funnily enough though, when-- that was when I was thinking of giving up on my film, and when I got the call from you-- I've written this in my book, so I'd better warn you-- that, I thought, "My God, this is a sign."

(Merlin) This was created by Jacob Epstein in 1910, 1911.

It's a remarkable piece of sculpture though, isn't it?

And it's now classified as a fully-- fully classified French historic monument.

(Rupert) Hm.

No, it is amazing.

(Merlin) I love the idea that this man is hounded out of England in 1897 when he comes out of prison, and he comes and he leads a fairly miserable life in Europe and particularly in Paris, and now he's buried here, and over a hundred years later, people came and they kissed his grave.

And I found that incredibly touching.

I used to pick up the little (speaking French) that people had written and left on the shelf and keep them in an envelope.

I don't know why, just sort of out of curiosity, I suppose.

And then the kissing started on the tomb, and I used to say that every kiss cost me a euro because it had to be cleaned, and it was beginning to deteriorate the whole fabric of the tomb.

(Rupert) I think it looks quite chic anyway.

(Merlin) It's a pity-- I think you said this to me one time-- it's a pity the public can't get up close and sort of embrace him.

(Rupert) I'm, of course, I'm fascinated by what's inside because one day, you're going to go into the tomb, aren't you, and have a look.

(Merlin) I'm steeling myself to open the door.

(Rupert) And I'm really hoping I'm going to be one of the people invited.

And do you think maybe when you die, you'll scatter something in there of yourself?

-Little pinch maybe.

-A little pinch?

(Merlin) Little pinch.

Um, I'm sure he wouldn't mind.

Isn't it bizarre in a way, this man who-- who finished up as a complete pariah in England, and now his grave is one of the most visited in the whole of Père Lachaise Cemetery.

(Rupert) Yeah, and also, he's the kind of Christ figure for the gay movement.

But at the same time, I think to sort of have him in a corner only as a gay martyr, um, I think is to not recognize other greatnesses that he had.

(Rupert) Absolutely.

Do you feel Oscar around sometimes?

(Merlin) I don't like to admit it, but... somewhere, yeah, there is a little bit.

If he left me anything, it's the, um, the ability to smile and shrug one's shoulders when things go wrong, which is-- he was an absolute master at.

(Rupert) Yes, I felt him very strongly the night of gay marriage in London because we were doing "The Judas Kiss" and, um, at 5:00, all the newspapers came out, the evening papers, with the ruling that gay marriage had been, um, gone through, and we were doing the show that evening, and you could tell that everybody coming into the theater had one thought, which was that this was the show to see that night.

And it felt just like the whole of history had kind of stood still, and going on stage that night, I never experienced a feeling so weird, and I really felt that Oscar was there then.

Well, we're going to meet again here, but not after six years, after one or two at the most.

(Rupert) To go inside?

-We'll see.

-We'll see.

Come on, then, let's go.

(mellow music) ♪ (Merlin) I think what we're left with today in his reputation and the way we see him and the works that he's left behind, um, and his rebellion against Victorian society and his individualism and his love of sensuality, these are all things which young people today say, "Yes, yes, these are the qualities I would love to have."

And that, I think, is partly the reason why he is so, still, loved and, to an extent, revered today.

(Gyles) Prophet, poet, playwright, icon--not just gay icon--icon.

And where is Carson now?

Today, saying I was gonna see you, I told the people what the program was about, they said, "Who is Edward Carson?"

Everybody in the world knows who Oscar Wilde is.

Nobody knows who Carson is.

Carson actually was genuine.

He really did believe in the union.

He believed in it passionately for all Ireland.

He was, if you like, a nationalist who saw the true Irish nationalism to be a happy partner within the union.

But as I say, he was-- although he was tremendously successful in so many ways, it was as though he had been caught in a major role in an Oscar Wilde play which would go on playing till the end of Carson's life.

(gentle music) ♪

Support for PBS provided by:

The Man Who Destroyed Oscar Wilde is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television