VPM News Focal Point

The fight to hold onto family property in Virginia

Clip: Season 3 Episode 7 | 17m 22sVideo has Closed Captions

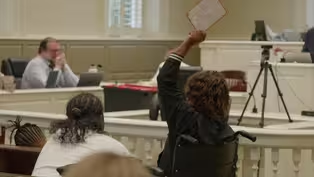

Kajsa Foskey is fighting to protect her families’ land in rural Louisa County.

In the early 1900s, Black Americans owned 19 million acres of land—today that number has dwindled to three million acres. Land loss often occurs when a landowner dies without a will. And when there is confusion about unpaid real estate taxes, the land is at risk of being auctioned by local governments. We speak with Kajsa Foskey, who is fighting to protect family land and Parker Agelasto.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

VPM News Focal Point is a local public television program presented by VPM

The Estate of Mrs. Ann Lee Saunders Brown

VPM News Focal Point

The fight to hold onto family property in Virginia

Clip: Season 3 Episode 7 | 17m 22sVideo has Closed Captions

In the early 1900s, Black Americans owned 19 million acres of land—today that number has dwindled to three million acres. Land loss often occurs when a landowner dies without a will. And when there is confusion about unpaid real estate taxes, the land is at risk of being auctioned by local governments. We speak with Kajsa Foskey, who is fighting to protect family land and Parker Agelasto.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch VPM News Focal Point

VPM News Focal Point is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipANGIE MILES: In the early 1900s, Black Americans owned as many as 19 million acres of land.

A number that has dwindled to just 3 million acres today.

One driver of land loss is complications that occur when a landowner dies without a will.

And in many cases, it is confusion over real estate taxes that puts land in jeopardy of being auctioned by local governments.

I'm joined now by Kajsa Foskey, who's an economic justice coordinator at the Virginia Poverty Law Center, where she works on heirs rights, and she has a personal connection to this issue as she works to protect her family's land in rural Louisa County.

Also, we have Parker Agelasto, who is the executive director of Capital Region Land Conservancy.

Thank you both for being with us.

PARKER AGELASTO: Thank you for having us.

KAJSA FOSKEY: Yeah.

Thank you for having us.

ANGIE MILES: So we know that land forfeiture laws and heirs property rights do pose some major challenges for many Virginians.

In your experience, how significant are these issues, either of you?

KAJSA FOSKEY: These issues are significant.

I think so many people underestimate the amount of land that was acquired in the Reconstruction era.

And since then, we've seen land loss in the millions of acres.

And a lot of that has to do with loss to forfeiture from property taxes through complications and passing down the will and the title being clouded because there's not clear title and families don't have clear ownership of the land.

And so I think the amount of land that has been lost, there is no solid number because so much of this property is still unaccounted for currently.

There's no bank of how much heirs property exist currently in the rural South.

And so we don't have a super strong understanding of how deeply this issue has affected Black landowners across the rural South.

ANGIE MILES: Parker, you want to weigh in?

PARKER AGELASTO: I think exactly that.

there is not a good metric to know.

We can look at some property records and, and say, well, if if the ownership says at all in the ownership record that it might be, tenants in common heirs property where there's a number of family members that own it.

But when you ask the question about, like, what is the effect of it, a lot of it means that this capital, this asset that is still the family's asset is not being put to productive use.

You cannot sell the timber on a property if you don't have clear title.

You can't sell the property if you don't have clear title.

You can't technically lease it to a farmer or somebody else to generate income if you don't have clear title.

And many times these properties have been in AA's status for maybe 60, 70, 80, maybe 100 years.

And you're talking about hundreds of descendants to try to come together, to reach consensus on how to resolve that.

And that can be a huge impact on people and their livelihood.

And then what's the use of these limited resources?

ANGIE MILES: So people have a better understanding of how confusing it can get.

So if great, say, grandmother has the land, passes it down, through just through the law when she passes away.

so maybe they're for children.

And then if each of them has for children.

Well, now you have, different layers, right, of inheritance.

And if one of her four children passes away, then all of their children, become potential heirs.

And then you have sort of, lines that are not parallel.

And then if you run out of the descendants in one line, then it kind of go back up to another.

It's like a big, confusing ball of yarn, isn't it?

KAJSA FOSKEY: Yeah, most definitely.

In the case of my family our heirs property was created when my great great-grandfather passed.

So that would be my grandfather's grandfather.

He had lots of children.

And so when he passed, that land would have gone to his wife and or his many children.

And since then, these are family members who are of my grandfather's generation.

They've many of them have had children, have had even great great-grandchildren.

And so the list of heirs is unbelievably long and almost feels impossible to actually build out a family tree that can stretch far enough to include horizontally the amount of heirs that could potentially be implicated in these heirs property issues.

ANGIE MILES: So, and not to mention the challenges for those trying to collect the taxes and trying to find and and notify everyone that the taxes are delinquent or that there might be a sale looming.

How has this affected your family, specifically in Louisa County?

And does that intersect with how you try to help others deal with their issues?

KAJSA FOSKEY: Yeah.

So my family, Louisa County, my great great-grandfather and my great great-grandmother both came into the marriage with land.

Some of that land was inherited post Reconstruction, post emancipation, and almost immediately after emancipation since the 1870s.

So this land has been passed down for so long.

And, since then, when my great, great grandfather died without a will and his wife was remaining, she actually did have a will.

And so his land was informally passed down to his heirs and her land.

She formally passed it down to one of her sons.

But, of course, eventually, her son had a will, and he passed that land down to his heirs.

But eventually, as time goes on, not everyone passes without a will, unfortunately.

And so some of our land has been lost due to, confusion over property taxes and we received a notice, back, I want to say this might have been 2012 or 2016, and they had 14 heirs listed on a notice for dealing with taxes owed to Louisa County.

Nine of those heirs were no longer living.

The remaining five would have been very young, children by the time the land became heirs property, they might have had very little connection to the land, might have never actually physically seen the land.

And so the land remaining in this state really does leave it vulnerable to a host of issues.

And unfortunately, we have lost land as a result of heirs property issues that just come from land being passed down informally and not having clear title, not knowing who's responsible for paying taxes, not knowing where the tax notices are even showing up.

That still remains a huge issue.

And to this day, the the land remains heirs property.

I have done such a deep dive into heirs property issues.

I've done such a deep dive into my family history, and even still, resolving it feels like such a heavy lift.

It feels like a huge mountain to climb.

And so that informs a lot of my work.

When I try to educate about heirs property issues and let families know what potential hurdles they might face when they're trying to resolve issues of their own within their own families.

ANGIE MILES: Parker... PARKER AGELASTO: If I can add... ANGIE MILES: Yes.

PARKER AGELASTO: Well it does.

And and part of the confusion is because you don't have an agreement amongst family members about how to manage the property and who is going to lead and run the point as the liaison with the local government for paying the taxes.

or managing the property when it comes to, well, if we're going to sell the property, everybody wants their equal share of the sale proceeds.

But when it comes to actually managing and the cost associated with maintaining and keeping that property, not everybody wants to share the cost.

So it becomes an issue of of trying to get in place some sort of a management agreement.

And oftentimes what gets recommended for families when they're resolving heirs property to try to keep it in the family is to establish an LLC, create a corporation of the family, and all the family members shares, then become part of that corporation.

And they can then, change and prorate it based on how family members might want to be involved in the property, or for those cousins that have never been to the property, who have no attachment to the property and aren't interested in in continuing a relationship to that property, give them an exit strategy that does not jeopardize the family ownership of the property.

What has happened often with heirs property and that has also led to the loss of heirs property in other cases is just who's paying the taxes.

But if you have a cousin who's got a small fractional share, they could potentially share your sell their undivided in interest to a third party who is not a family member.

And that third party now has a voice in how the property is going to be managed or potentially sold and forced into a partition, which is a court ordered procedure that divides up the land for all the heirs and as you might know, it's it's better to have, for economies of scale one big farm than 50 little farms.

Sometimes the 50 little farms aren't even economically viable.

So that becomes another issue in how to keep land in the family.

And even with who's paying the taxes.

ANGIE MILES: So let me just ask, philosophically speaking, neither of you has an issue with the fact that localities need to collect taxes, right?

They need to pay for services and salaries.

And so philosophically, you're not saying that real estate taxes are a bad thing.

Is that correct?

PARKER AGELASTO: I personally think that real estate, it's tha thats the law.

And if you own real estate or if you own real property that is taxable, you pay your taxes.

Okay.

I do think, however, that there are instances where what is the assessment and what is the tax rate that is applied that's that subjective.

That can be up to the locality determined.

And frankly, from my perspective, I'd love to see Virginia adopt a standard where you could have a little bit more of a homesteading where the tax rate was different based on how long you've been on the land.

ANGIE MILES: Okay.

You know, you shouldn't have to lose your land because of tax rate changes or your assessment has changed so you can no longer afford to pay.

ANGIE MILES: So let's get to that Because in speaking with people about this, I've heard complaints about overassessment.

You know, there's nothing but a shack there.

But suddenly my property values gone up, which means my taxes have gone up and I'm not even living there.

I've heard stories of people having to harvest all the timber to maintain the taxes when the land has been in the family for a long, long time.

Localities do have to follow the code of Virginia and how they handle the sales waiting periods.

For example, before an auction, safeguards for people with approvals through the courts, ways to redeem land, ways to appeal sales.

But still, it does seem that counties have a lot of power, that localities have a wide range of discretion about what they do and how they do it, and it impacts real people in their ownership.

You want to say something about that?

KAJSA FOSKEY: Yeah.

So a lot of my work and studying heirs property and a lot of the scholarship that I found related to the solutions for heirs property have really been I've focusing on resolving the clear title issue, getting in in one person's name, getting everything back into good standing.

And I think that a lot of the solutions that are around our property tax system, around addressing years property issues, don't always take into account the real lived experiences in the historical context that creates how Black families use and understand their land and care to manage their land in the future.

So fundamentally, I don't have a problem with property taxes.

I don't think property taxes are inherently the issue.

But I think what has happened is that our property laws have been created to really protect one type of property ownership, and in doing that, we have neglected a subset of communities in America that have used their properties differently.

They have used their lands communally.

Right.

So families who want to leave their land to their many heirs now have to conform to a system where one person has to pay the taxes, or they have to come up with some informal agreement amongst themselves.

And so there have been efforts, I think, to address some of the issues around tax assessments and tax collection.

There was a bill in the legislature last year that would have allowed families to have more time to pay back, owed taxes to get on a payment plans.

But would that also would have done what it would have allowed families to have one year to buy back their properties if they lost it, to attack sale and in doing that, that was a tool really, to help families have more time to come together, to pool money, to find other resources, to be able to continue to protect their land.

And I think that a lot of the solutions are going to have to really take into account that there has been this new form of property ownership that has informally existed in our ecosystem.

and we now have to account for that and create some real protections that help those families who have been historically vulnerable to tax loss, exploitation, etc., really help them protect the assets that they have that can really help even propel them into further economic opportunities.

I think land has been contrived as something that's supposed to be a wealth generating asset.

And I think for many black families, unfortunately, that hasn't been the case.

ANGIE MILES: Laws certainly do change and the long ago history the ‘long ago history people could just pay the taxes on property and then own it.

There have been a number of people who've become wealthy by just paying attention to who was behind on their taxes, and then paying that tax and then acquiring the land.

That is no longer the law in Virginia.

Some other things have changed, like, the ease of partition, developments for land heirs.

Right.

Parker, can you speak about some of the changes you've seen in the way the law handles this?

I think what you're referring to, it's called the Uniform Petition of Heirs Property.

And that is a change that, was enacted by the General Assembly in Virginia a few years ago.

And it was something that was important that a uniform law is something that, has been established by the Uniform Law Commission, and it's a way to help address, a universal problem, something that is nationwide.

And Virginia became one of the first states in the South, to really adopt this, Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act.

And it's an important thing because it now puts into law the process by which heirs property can be resolved in a court.

So if you can't get family members to necessarily come together cooperatively in agreement, you still have the ability to go to the court.

And they have the ability to say, well, we can either partition it.

And that example that I was giving us, let's say you have property and it gets divided up 50, 50 ways.

You may not be able to even build a house on it.

you can't really divide one house of 50 ways.

And so the courts now have a system in place how to resolve this.

It takes into consideration those lived experiences and who, who would be prioritized above the rest.

So if there's somebody living on the property who is truly a residential, steward, they get prioritized above the person who's not even a family member, but bought in on an undivided interest.

And it helps to establish the process through which you come up with a an agreed upon value for the land.

You know, I might disagree with my brother about what's the value of Mom and Dad's property.

Well, that gets exacerbated when you have a lot more people and some people who are living in localities where land is worth very different amounts than what we experience in Virginia or in rural communities and their perceptions are different.

And so it allows to establish what the values would be.

And then the process for family members to kind of buy out other family members, other at that rate.

But again, it's about who can get a loan to then buy out their some family members to try to even keep the property in the in ownership.

So it is certainly a ball of yarn, right.

That can get very complicated.

And it's very frustrating and sometimes deeply painful for people to work on these issues.

We're going to rely on the two of you to help us with the compilation of resources that we can share out on our website for individuals who really are looking for help, may have limited or no resources and need answers.

And, you too, fortunately, are a wealth of knowledge and can help us to direct them, to more information.

So thank you both for joining us for this discussion.

KAJSA FOSKEY: Thank you.

PARKER AGELASTO: Thanks Angie.

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep7 | 2m 2s | A ferry run for over 200 years is now shut down (2m 2s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep7 | 10m 47s | The delinquent tax property auction is an everyday occurrence in America. Should it be? (10m 47s)

Reclaimed Land on the Mattaponi

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep7 | 3m 23s | An Indigenous tribe used a federal grant to reclaim 855 acres. (3m 23s)

Role of civil asset forfeiture in Virginia’s justice system

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep7 | 4m 3s | Exploring civil asset forfeiture laws in Virginia and its true role in our justice system (4m 3s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- News and Public Affairs

Top journalists deliver compelling original analysis of the hour's headlines.

- News and Public Affairs

FRONTLINE is investigative journalism that questions, explains and changes our world.

Support for PBS provided by:

VPM News Focal Point is a local public television program presented by VPM

The Estate of Mrs. Ann Lee Saunders Brown